Image via Wikipedia

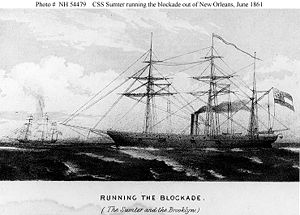

Image via WikipediaOn Sunday, June 30, 1861, Raphael Semme's career as a commerce raider for the Confederacy began. His warship, the C.S.S. Sumter, ran the blockade at the mouth of the Mississippi River and escaped to the high seas.

Commerce raiding is a form of naval warfare in which one side, almost always the weaker power, attacks the merchant shipping of the other side. In the case of the Confederacy, whose navy was almost nonexistent at this time, the principle goal was to force the Union to deploy ships to protect the merchant ships, weakening the blockade of Southern ports.

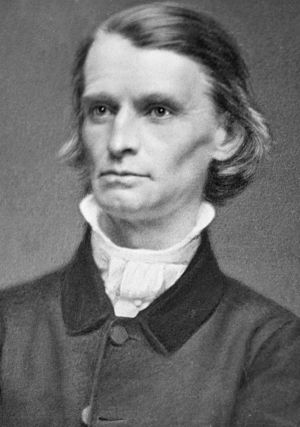

Semmes was a 35-year veteran of the U.S. Navy. Born in Maryland and living in Alabama when the war began, he resigned his commission and joined the Confederate Navy. He was soon sent to New Orleans where he began to convert a steamer, the Havana, into a cruiser. The conversion was complete on June 3, but Semmes found all avenues of escape blocked by Union warships.

On June 21, the U.S.S. Powhatan left her station. Semmes took the Sumter to Pass a l'Outre, but was unable to find a river pilot who would guide him past the mud bars at the mouth of the Mississippi before the Powhatan returned.

Finally, on June 30, the U.S.S. Brooklyn left her station to pursue another ship. Semmes took advantage and sped toward the Gulf. One river pilot lost his nerve, claiming he hadn't been through this pass in three months, but another soon arrived to take the Sumter out.

The Brooklyn spotted the Sumter and broke off its pursuit of the other vessel to give chase -- a chase that would last over four hours before the Brooklyn finally gave it up and returned to her post.

Over the next six months, Semmes and the Sumter would disrupt shipping in the Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea, capturing 17 merchant ships. It all came to an end in January 1862 at Gibraltar. The Sumter was in for repairs when Union ships blockaded the port. Semmes decommissioned the Sumter and sold her, then escaped to England.