There had been few full generals in American history -- George Washington was a rare exception -- but on Saturday, August 31, 1861, the Confederate Congress confirmed five full generals who had been appointed by President Jefferson Davis.

The five, in order of seniority, were Samuel Cooper, Albert Sidney Johnston, Robert Edward Lee, Joseph Eggleston Johnston and Pierre Gustav Toutant Beauregard.

The appointments would cause some animosity between Davis and Joe Johnston. Confederate law stated that generals of identical commissions would have seniority according to the rank they had held in the U.S. Army. Johnston, who had held the rank of brigadier general in the old Army, was insulted to discover that he was now ranked fourth behind men who had been colonels in the U.S. Army.

In Davis's opinion, the determining factor was line commissions versus staff commissions. Johnston had held a staff position. Johnston was angered to discover that the three men who outranked him were all close friends of Davis.

Johnston, on September 12, would write a lengthy, passionate letter, "my earnest protest against the wrong which I conceive has been done me." Davis dismissed it with a two-sentence reply: "Sir: I have just received and read your letter of the 12th instant. Its language is, as you say, unusual; its arguments and its statements utterly one-sided, and its insinuations as unfounded as they are unbecoming."

Wednesday, August 31, 2011

Tuesday, August 30, 2011

150 Years Ago -- Fremont's Proclamation

On August 30, 1861, Union General John Frémont, commanding the Department of the West, issued an emancipation proclamation and confiscation act, stating, "The property, real and personal, of all persons in the state of Missouri who shall take up arms against the United States, or who shall be directly proven to have taken an active part with their enemies in the field, is declared to be confiscated to the public use, and their slaves, if any they have, are hereby declared freemen."

Since Union General John Frémont had arrived in St. Louis, Missouri, on July 25 to take command of the Department of the West, his reputation had quickly plummeted. The influential Blair family had urged his appointment, but had quickly turned against him, blaming him, among other things, for the death of Nathaniel Lyon, another Blair family favorite, and for the disaster that had befallen the main Union army in the west at Wilson's Creek.

Frémont had much to do -- he was expected to secure the state and plan an expedition down the Mississippi toward New Orleans -- but had little in the way of men or equipment to get the job done. Guerrilla warfare was rapidly becoming rampant in the state, St. Louis seemed to be a hotbed of secessionist activity --Frémont had declared martial law in the city and suppressed two local newspapers on August 14 -- and there was also the problem of the combined army of Confederate/Arkansas/Missouri militia that had defeated Lyon at Wilson's Creek.

Luckily for Frémont, the pro-Southern forces had not followed up on their victory. Ben McCulloch, commander of the Confederate forces, had not wanted to enter Missouri, and now couldn't be persuaded to pursue the defeated Federals to Rolla. The Arkansans, their terms of enlistment nearing an end, had returned home, leaving Sterling Price's state militia force to go it alone.

Frémont had the makings of a good plan to secure the state. Union troops under John Pope were already in the northeastern part of Missouri, stamping out the guerrilla warfare there. Frémont proposed to hold the railroads radiating out from St. Louis by fortifying and garrisoning Rolla, Jefferson City and Ironton. He would protect the Mississippi by fortifying Cape Girardeau, St. Louis and Cairo, Illinois. When all that was done "my plan is New Orleans straight."

One of the few good decisions Frémont would make during his time at St. Louis was to select the right man to command the force at Cairo, Illinois: Ulysses S. Grant. Grant was nominated as a brigadier general of volunteers on July 31. When his father learned of his promotion, he wrote, saying, "Ulyss, this is a good job, don''t lose it."

But two other problems were causing Washington to take a negative view of Frémont. The first was that he needed all kinds of military equipment in a big hurry. This would almost always cause a lot of irregularities and graft. In fact, the War Department was also experiencing some of the same problems on a national scale, which would soon lead to Simon Cameron's ouster from his position as Secretary of War.

This rapid arming of his troops probably exacerbated the problems Frémont was having with the Blairs. They were not getting what they thought was their rightful share of the action.

The other problem was Frémont's headquarters. From Terrible Swift Sword by Bruce Catton:

"It began with the headquarters itself -- with the look of it, the atmosphere that pervaded it, and the people who were visible there. Headquarters had been housed in a good three-story dwelling that lay behind a pleasant lawn enclosed by a stone wall, at Chouteau Avenue and Eighth Street, rented for $6000 a year. The building was not actually too big and although the price was high it perhaps was not really excessive, in view of the fact that this was one of the most important military departments in the United States; but somehow the place seemed a little too imposing. Frémont had guards all over the premises, and there were staff officers to sift his callers -- the unending stream of people who simply had to see the general, most of whom had no business getting within half a mile of him -- and presently people were muttering that the man lived in a vast mansion and surrounded himself with the barriers of a haughty aristocracy.

"Many of these complaints reflected nothing more than the inability of a young republic to understand that an overburdened executive must shield himself if he is to get any work done. (After all, this was the era when the White House itself was open to the general public, so that any persistent citizen could get in, shake the hand of the President and consume time which that harassed official could have used in more fruitful ways.) But it is also true that Frémont brought a great many of these complaints on himself by his inability to surround himself with the right kind of assistants.

"Frémont had a fatal attraction for foreigners -- displaced revolutionists from the German states, from Hungary and from France, fortune hunters from practically everywhere, men who had been trained and commissioned in European armies but who knew nothing at all about this western nation whose uniforms they wore and whose citizens they irritated with their heel-clickings and their outlandish mangling of the American idiom. Frémont was taking part in a peculiarly American sort of war -- Price's backwoods militia was wholly representative -- and Missouri had felt from the beginning that the German-born recruits from St. Louis were a little too prominent. Now headquarters had this profoundly foreign air, and when a man was told that he could not see the general -- to sell a load of hay or a tugboat, to apply for a commission, to give a little information about Rebel plots, or just to pass the time of day -- he was given the bad news in broken English by a dandified type who obviously belonged somewhere east of the Rhine. It was all rather hard to take."

By the end of August 1861, it was all getting to be rather hard to take for Frémont as well. He felt he needed some grand gesture that would set everything right, and thus came his proclamation to the people of Missouri:

Head-quarters of the Western Department,

St. Louis, August 31, 1861.

Circumstances, in my judgment of sufficient urgency, render it necessary that the Commanding General of this Department should assume the administrative powers of the State. Its disorganized condition, the helplessness of the civil authority, the total insecurity of life, and the devastation of property by bands of murderers and marauders who infest nearly every county in the State and avail themselves of the public misfortunes and the vicinity of a hostile force to gratify private and neighborhood vengeance, and who find an enemy wherever they find plunder, finally demand the severest measure to repress the daily increasing crimes and outrages which are driving off the inhabitants and ruining the State. In this condition the public safety and the success of our arms require unity of purpose, without let or hindrance, to the prompt administration of affairs.

In order, therefore, to suppress disorders, to maintain as far as now practicable the public peace, and to give security and protection to the persons and property of loyal citizens, I do hereby extend, and declare established, martial law throughout the State of Missouri. The lines of the army of occupation in this State are for the present declared to extend from Leavenworth by way of the posts of Jefferson City, Rolla, and Ironton, to Cape Giradeau on the Mississippi River.

All persons who shall be taken with arms in their hands within these lines shall be tried by court-martial, and, if found guilty, will be shot. The property, real and personal, of all persons in the State of Missouri who shall take up arms against the United States, and who shall be directly proven to have taken active part with their enemies in the field, is declared to be confiscated to the public use; and their slaves, if any they have, are hereby declared free.

All persons who shall be proven to have destroyed, after the publication of this order, railroad tracks, bridges, or telegraphs, shall suffer the extreme penalty of the law.

All persons engaged in treasonable correspondence, in giving or procuring aid to the enemies of the United States, in disturbing the public tranquility by creating and circulating false reports or incendiary documents, are in their own interest warned that they are exposing themselves.

All persons who have been led away from their allegiance are required to return to their homes forthwith; any such absence without sufficient cause will be held to be presumptive evidence against them.

The object of this declaration is to place in the hands of the military authorities the power to give instantaneous effect to existing laws, and to supply such deficiencies as the conditions of war demand. But it is not intended to suspend the ordinary tribunals of the country, where the law will be administered by the civil officers in the usual manner and with their customary authority, while the same can be peaceably exercised.

The Commanding General will labor vigilantly for the public welfare, and in his efforts for their safety hopes to obtain not only the acquiescence, but the active support of the people of the country.

J. C. Fremont,

Major-General Commanding.

The proclamation was quickly printed and made public. Frémont also sent a copy to Washington for the president's input.

Related articles

- 150 Years Ago: Fremont Takes Command in the West (civilwarmeanderings.blogspot.com)

- 150 Years Ago: Changes (civilwarmeanderings.blogspot.com)

- 150 Years Ago -- A Lull (civilwarmeanderings.blogspot.com)

- 150 Years Ago -- The Battle of Wilson's Creek (civilwarmeanderings.blogspot.com)

Labels:

150 Years Ago,

1861,

John Fremont,

Missouri,

slavery,

Ulysses S. Grant

Monday, August 29, 2011

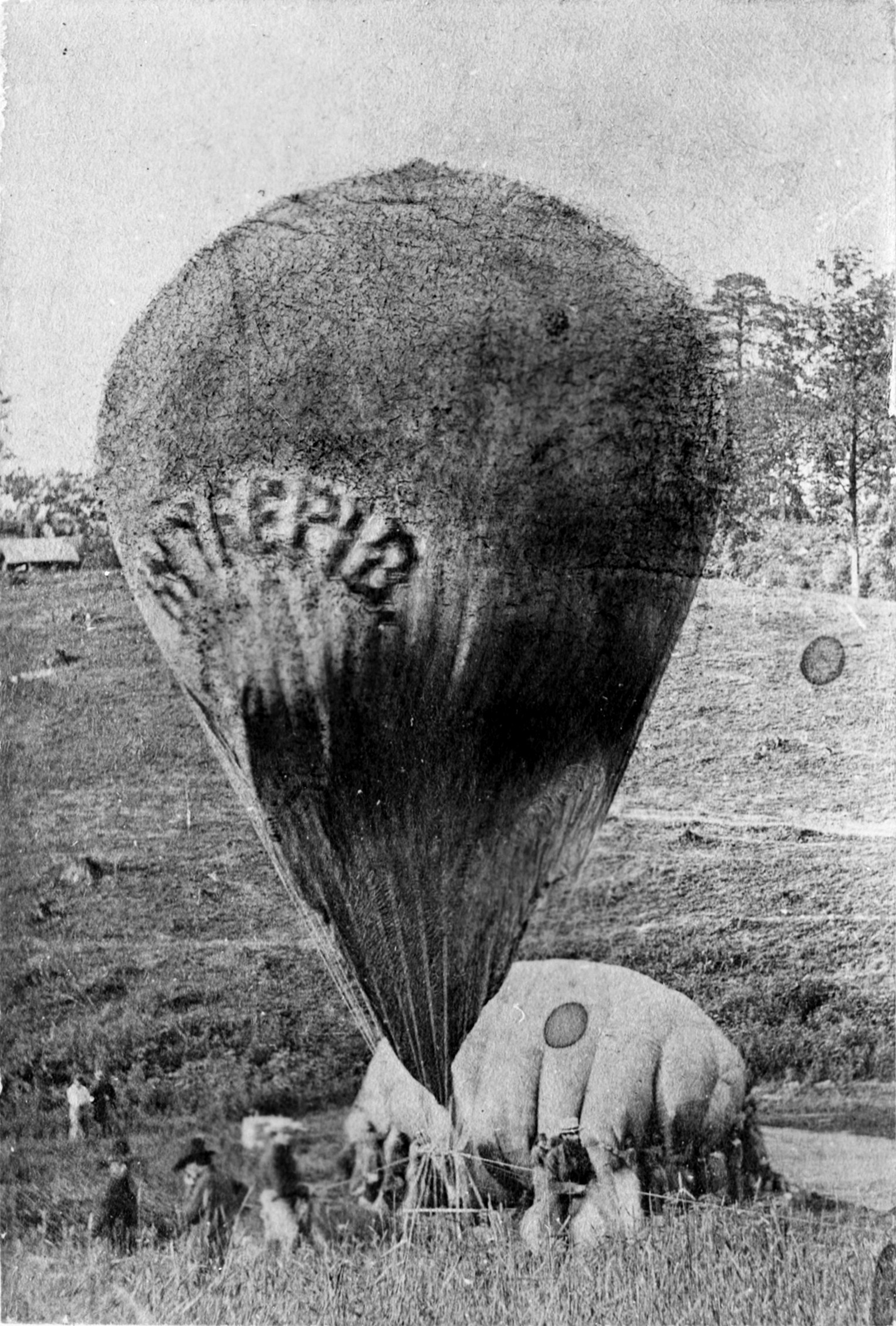

150 Years Ago -- Establishing a Balloon Corps

Image via Wikipedia

Image via WikipediaThaddeus Lowe had put his dream of making a transatlantic balloon flight on hold to offer his services to his country. In June 1861, he had demonstrated the military usefulness of his balloon to President Lincoln, then to a group of skeptical generals.

Lowe hoped to become the "chief aeronaut" of a balloon corps dedicated to aerial reconnaissance, but had competition from several other balloonists, including John Wise, John La Mountain, and the Allen brothers, Ezra and James. After his successful demonstrations, he was asked to submit an estimate for the cost of making suitable balloons, but was soon informed that he had been underbid by Wise.

In mid-July, Lowe was conducting experiments on the grounds of the Smithsonian Institution when Captain Amiel Whipple of the U. S. Topographical Engineers sent him a message. General Irvin McDowell was at Centreville, Virginia, and needed a balloon to conduct aerial reconnaissance of the Confederate position at Bull Run. Wise had not shown up. Whipple asked Lowe to bring his balloon down.

Since Lowe did not have a portable hydrogen gas generator it was necessary to inflate the balloon in Washington and tow it south. Lowe was inflating his balloon at a gas main near the Columbian Armory when Wise finally showed up. Lowe was ordered to disconnect his balloon and make way for Wise to inflate his.

Wise inflated his balloon and twenty men from the 26th Pennsylvania began the task of towing the balloon into central Virginia. Along the way, Wise's balloon snagged on a low-hanging tree branch and burst.

Lowe inflated his balloon and started south. He made it as far as Fall Church, where he learned of the Union army's rout at Bull Run. Lowe remained where he was as the retreating army streamed past him. When the last of the Federal pickets withdrew, Lowe started back toward Arlington, dragging his balloon in a heavy rainstorm. He arrived at Fort Corcoran the evening after the battle with the balloon still fully inflated.

Two days later, when the weather finally cleared, Lowe made a free ascent and observed the victorious Rebel army still concentrated around the Manassas area. The news was welcome in Washington, relieving tensions of an expected invasion.

But before Lowe could get the news back to the city, he had a serious misadventure. As he returned to the Union lines, soldiers, thinking Confederates were piloting the craft, began firing on Lowe and demanding that he show his colors. Lowe had no flag to show, so he stayed aloft and finally landed in a grove of trees a couple of miles outside the Union lines. He was discovered by men from the 31st New York Volunteers, but he had twisted his ankle in the landing and could not walk out with them. It was up to his wife to rescue him. She procured a wagon, disguised herself as a farm woman and drove south to pick him up. Lowe and his balloon were hidden in the bottom of the wagon and driven past Confederate pickets at dusk.

Lincoln ordered General-in-Chief Winfield Scott to form a balloon corps with Lowe as chief aeronaut. On August 2, Lowe received his orders and instructions:

HEADQUARTERS DEPARTMENT OF NORTHEASTERN VIRGINIA,Mr. T. S. C. LOWE,

Arlington, August 2, 1861.

Aeronaut:

SIR: You are hereby employed to construct a balloon for military purposes capable of containing at least 25,000 cubic feet of gas, to be made of the best India silk, not inferior to the sample which is divided between us, you retaining a part, with best linen network, and three guys of manilla cordage from 1,200 to 1,500 feet in length. The materials you will purchase immediately, the best the markets afford and at prices not exceeding ordinary rates; and the bills you will forward to me through Maj. Hartman Bache, chief of the Corps of Topographical Engineers. When these materials shall have been collected at Philadelphia, where the balloon is to be constructed, you will report to me, that I may send an officer of the corps to inspect them. You need not, however, wait for the inspecting officer, but go on rapidly with the work, with the understanding that it may be suspended, provided that upon examination the materials or work prove unsatisfactory.

Your compensation from the day of collecting the materials and during the time of making the balloon shall be $5 per day, provided that a reasonable time be allowed for the collection and ten days for making. From and after the day that the balloon shall be ready for inflation at Washington, D.C., your compensation will be $10 per day as long as the Government may require your services.

Inclosed herewith is an order authorizing the purchase of materials necessary for the operation with which you are charged.Very respectfully,

A. W. WHIPPLE,

Captain, Topographical Engineers.[Inclosure.]HEADQUARTERS DEPARTMENT OF NORTHEASTERN VIRGINIA.Mr. T. S. C. Lowe, aeronaut, is hereby authorized to purchase 1,200 yards of best India silk and sufficient linen thread, cordage, &c., for the construction of a balloon, and all reasonable bills for the same, when presented to me through the Bureau of Topographical Engineers, will be paid.A. W. WHIPPLE,

Captain, Topographical Engineers.

Lowe began construction of this new balloon, the Union, and also began assembling and training a group of men in the art of military ballooning. The Union Army Balloon Corps remained a civilian contract organization without military commissions. This put the group in a somewhat precarious situation. If any of the men were ever captured by Confederate troops they could be classified as spies and executed. The Balloon Corps would eventually consist of seven aircraft.

The Union was completed on August 28, and Lowe was ordered to bring it to Fort Corcoran. Because he still did not have a portable gas generator, Lowe was confined to operations near Washington, but the balloon stayed in constant use for almost two months.

Related articles

- 150 Years Ago: Ballooning (civilwarmeanderings.blogspot.com)

- 150 Years Ago: Boonville and Greeneville (civilwarmeanderings.blogspot.com)

Friday, August 26, 2011

150 Years Ago -- Cross Lanes

On Monday, August 26, 1861, the Battle of Cross Lanes took place in western Virginia.

Confederate troops under Brigadier General John Floyd crossed the Gauley River and attacked the 7th Ohio Regiment at Kessler's Cross Lanes. It was an overwhelming assault that surprised the Federals while they were having breakfast. It lasted just a few moments before the Federals broke and ran, leaving behind about 40 dead and 100 prisoners.

Confederate troops under Brigadier General John Floyd crossed the Gauley River and attacked the 7th Ohio Regiment at Kessler's Cross Lanes. It was an overwhelming assault that surprised the Federals while they were having breakfast. It lasted just a few moments before the Federals broke and ran, leaving behind about 40 dead and 100 prisoners.

Wednesday, August 24, 2011

150 Years Ago -- European Commissioners

On Saturday, August 24, 1861, Confederate President Jefferson Davis named his European commissioners -- Pierre Rost (Spain), James Mason (Great Britian) and John Slidell (France).

Tuesday, August 23, 2011

150 Years Ago -- Rose Greenhow Is Arrested

Image via Wikipedia

Image via WikipediaOn Friday, August 23, 1861, Allan Pinkerton apprehended Rose Greenhow for spying and placed her under house arrest.

Maria Rosatta O'Neal was born on a farm in southern Maryland in 1817. Her father was murdered by his slaves when Rose was just a child. The family became destitute. When Rose was 14, she and her sister Ellen went to live with an aunt, Maria Ann Hill, who ran the Congressional Boarding House across the street from the Capitol.

The boardinghouse was a center of Washington society. Senators, congressmen, and other dignitaries lodged there, including John C. Calhoun, who was an important influence on Rose, transforming her into a self-described "Southern woman, born with revolutionary blood in my veins."

Rose was initially snubbed as a nobody, but soon found her place in Washington society. When she was 18, she married one of Washington's most eligible bachelors, Dr. Robert Greenhow. He had a law degree and a medical degree and was one of the highest-ranking members of the State Department.

When the Civil War began, Rose was a widow and a grande dame of Washington society. At the center of everything that was anything in Washington, Rose soon was at the center of a vast espionage network. She was now in her mid-40's and still a striking beauty. She used her "almost irresistible seductive powers" to learn everything she could about General Irvin McDowell's army and passed the information along to General P. G. T. Beauregard in Virginia.

Acting on a tip, Allan Pinkerton, the head of the new Union Intelligence Service, placed Greenhow under surveillance. On the evening of August 22, Pinkerton witnessed a Union officer giving military information to Greenhow. She was arrested the next day. A search of her house turned up a diary with several pages of notes, copies of orders from the War Department, and other incriminating documents.

Although under house arrest, Greenhow barely slowed her espionage activities for the Confederacy. In January of 1862, she would be transferred to Old Capitol Prison.

Labels:

150 Years Ago,

1861,

Allan Pinkerton,

Rose Greenhow

Saturday, August 20, 2011

150 Years Ago -- Ordinance of Dismemberment

Image via Wikipedia

Image via WikipediaThe Unionists of western Virginia were still trying to secede from the seceders. On Tuesday, August 20, 1861, the Wheeling Convention passed an "ordinance of dismemberment" by a vote of 50-28, creating a new state to be called "Kanawha" out of 39 Virginia counties west of the Shenandoah Valley. The ordinance provided for an election on October 24 to choose delegates to a constitution convention. The voters would also choose between "for a new State" or "against a new State."

Labels:

150 Years Ago,

1861,

western Virginia,

Wheeling Convention

Friday, August 19, 2011

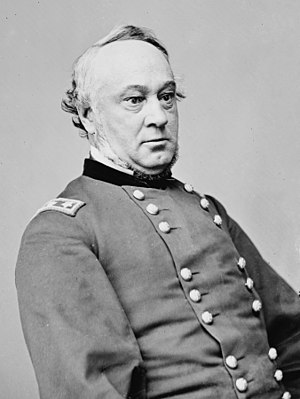

150 Years Ago -- Henry Halleck's Promotion

Image via Wikipedia

Image via WikipediaAugust 19, 1861: The effective date of Henry Halleck's promotion to major general, making him the fourth-highest ranking officer in the U.S. Army after General-in-chief Winfield Scott, George McClellan and John Frémont.

Scott recommended Halleck for the promotion in consideration of his reputation as a military genius. Halleck, a New Yorker, attended Hudson Academy and Union College, then West Point, graduating third in the class of 1839. During his 15 years of service in the U.S. Army, he constructed seacoast defenses, studied French military tactics, lectured, wrote, taught.

He was assigned to California during the Mexican War, eventually serving under General Bennet Riley, the governor general of the California Territory. Halleck was appointed military secretary of state and was one of the principal authors of the state constitution. Halleck retired from the army in 1854. When the Civil War began, he was amassing a fortune as a lawyer and land speculator in San Francisco.

Also on this date, the Confederate Congress passed a bill admitting Missouri into the Confederacy. The bill did not mean much as it recognized the government of Governor Claiborne Jackson as the legal authority to ratify the constitution. That government had been deposed and replaced with a more Unionist body.

Wednesday, August 17, 2011

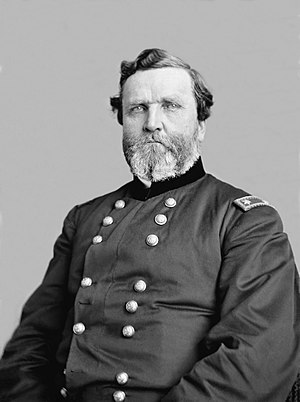

150 Years Ago -- George Thomas's Promotion

Image via Wikipedia

Image via WikipediaOn August 17, 1861, George Thomas was promoted to brigadier general of volunteers. This was his third promotion in the last four months. He would serve under Major General Robert Anderson in Kentucky, commanding an independent force in the eastern part of the state.

Thomas graduated from West Point in 1840, twelfth in his class, then served in the Seminole and Mexican Wars. Thomas suffered an arrow wound in the chest during a fight with a Comanche warrior in August 1860. Later that year, he fell off a train platform in Lynchburg, Virginia, severely injuring his back.

When the Civil War began, Thomas was serving in the 2nd U.S. Cavalry. 19 of the 36 regimental officers, including three of Thomas's superiors, Albert Sidney Johnston, Robert E. Lee, and William Hardee, resigned to join the Confederacy, but Thomas, a Virginia native, remained loyal to the Union. Many members of his family never spoke to him again.

Related articles

- 150 Years Ago -- Robert Anderson and the Department of the Cumberland (civilwarmeanderings.blogspot.com)

Tuesday, August 16, 2011

150 Years Ago -- Lincoln States the Obvious

On Friday, August 16, 1861, President Abraham Lincoln issued a proclamation officially declaring that the Confederate States "are in a state of insurrection against the United States." Lincoln also declared "that all

commercial intercourse (between the North and South) should forthwith cease and desist."

Also on this date, in New York, a United States Circuit Court grand jury brought in an interesting presentment, accusing several newspapers of treason and asking the court's advice:

By the President of the United States of America

A Proclamation

Whereas on the 15th day of April, 1861, the President of the United States, in view of an insurrection against the laws, Constitution, and Government of the United States which had broken out within the States of South Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, Florida, Mississippi, Louisiana, and Texas, and in pursuance of the provisions of the act entitled "An act to provide for calling forth the militia to execute the laws of the Union, suppress insurrections, and repel invasions, and to repeal the act now in force for that purpose," approved February 28, 1795, did call forth the militia to suppress said insurrection and to cause the laws of the Union to be duly executed, and the insurgents have failed to disperse by the time directed by the President; and

Whereas such insurrection has since broken out, and yet exists, within the States of Virginia, North Carolina, Tennessee, and Arkansas; and

Whereas the insurgents in all the said States claim to act under the authority thereof, and such claim is not disclaimed or repudiated by the persons exercising the functions of government in such State or States or in the part or parts thereof in which such combinations exist, nor has such insurrection been suppressed by said States:

Now, therefore, I, Abraham Lincoln, President of the United States, in pursuance of an act of Congress approved July 13, 1861, do hereby declare that the inhabitants of the said States of Georgia, South Carolina, Virginia, North Carolina, Tennessee, Alabama, Louisiana, Texas, Arkansas, Mississippi, and Florida (except the inhabitants of that part of the State of Virginia lying west of the Alleghany Mountains and of such other parts of that State and the other States hereinbefore named as may maintain a loyal adhesion to the Union and the Constitution or may be from time to time occupied and controlled by forces of the United States engaged in the dispersion of said insurgents) are in a state of insurrection against the United States, and that all commercial intercourse between the same and the inhabitants thereof, with the exceptions aforesaid, and the citizens of other States and other parts of the United States is unlawful, and will remain unlawful until such insurrection shall cease or has been suppressed; that all goods and chattels, wares and merchandise, coming from any of said States, with the exceptions aforesaid, into other parts of the United States without the special license and permission of the President, through the Secretary of the Treasury, or proceeding to any of said States, with the exceptions aforesaid, by land or water, together with the vessel or vehicle conveying the same or conveying persons to or from said States, with said exceptions, will be forfeited to the United States; and that from and after fifteen days from the issuing of this proclamation all ships and vessels belonging in whole or in part to any citizen or inhabitant of any of said States, with said exceptions, found at sea or in any port of the United States will be forfeited to the United States; and I hereby enjoin upon all district attorneys, marshals, and officers of the revenue and of the military and naval forces of the United States to be vigilant in the execution of said act and in the enforcement of the penalties and forfeitures imposed or declared by it, leaving any party who may think himself aggrieved thereby to his application to the Secretary of the Treasury for the remission of any penalty or forfeiture, which the said Secretary is authorized by law to grant if in his judgment the special circumstances of any case shall require such remission.

In witness whereof I have hereunto set my hand and caused the seal of the United States to be affixed.

Done at the city of Washington, this 16th day of August, A.D. 1861, and of the Independence of the United States the eighty-sixth.

ABRAHAM LINCOLN.

By the President:

WILLIAM H. SEWARD,

Secretary of State.

To the Circuit Court of the United States for the Southern District of New York:

The Grand Inquest of the United States of America for the Southern District of New York, beg leave to present the following facts to the Court, and ask its advice thereon:

There are certain newspapers within this district which are in the frequent practice of encouraging the rebels now in arms against the Federal Government by expressing sympathy and agreement with them, the duty of acceding to their demands, and dissatisfaction with the employment of force to overcome them. These papers are the New York daily and weekly Journal of Commerce, the daily and weekly News, the daily and weekly Day Book, the Freeman's Journal, all published in the city of New York, and the daily and weekly Eagle, published in the city of Brooklyn. The first-named of these has just published a list of newspapers in the Free States opposed to what it calls “the present unholy war” --a war in defence of our country and its institutions, and our most sacred rights, and carried on solely for the restoration of the authority of the Government.

The Grand Jury are aware that free governments allow liberty of speech and of the press to their utmost limit, but there is, nevertheless, a limit. If a person in a fortress or an army were to preach to the soldiers submission to the enemy, he would be treated as an offender. Would he be more culpable than the citizen who, in the midst of the most formidable conspiracy and rebellion, tells the conspirators and rebels that they are right, encourages them to persevere in resistance, and condemns the effort of loyal citizens to overcome and punish them as an “unholy war” ? If the utterance of such language in the streets or through the press is not a crime, then there is a great defect in our laws, or they were not made for such an emergency.

The conduct of these disloyal presses is, of course, condemned and abhorred by all loyal men; but the Grand Jury will be glad to learn from the Court that it is also subject to indictment and condign punishment.

All which is respectfully presented.

New York, August 16, 1861.

Charles Gould, Foreman.

Monday, August 15, 2011

150 Years Ago -- Robert Anderson and the Department of the Cumberland

Image of Robert Anderson via Wikipedia

Image of Robert Anderson via WikipediaOn Thursday, August 15, 1861, Union Brigadier General Robert Anderson, the hero of Fort Sumter, was appointed to command of the newly-formed Department of the Cumberland, comprising most of the states of Kentucky and Tennessee.

Anderson would relinquish command of the department to Brigadier General William Tecumseh Sherman in October. Ill health is often cited as the reason for the change in command, but Anderson, who was reluctant to distribute arms to Kentucky Unionists, might have fallen out of favor with Lincoln.

The Department of the Cumberland would cease to exist in October, becoming a part of the Department of the Ohio, but would be resurrected in October 1862, with General William Rosecrans commanding.

Sunday, August 14, 2011

150 Years Ago -- Mutiny

On Wednesday, August 14, 1861, Union General George McClellan put down a mutiny in his army by men of the 79th New York Infantry Regiment.

The 79th New York, originally organized in July 1859 as a Scottish-American fraternity in New York City, was quickly mobilized after Fort Sumter. Some recruitment brought the unit up to strength, then they marched down Broadway to Washington.

At the Battle of Bull Run, the 79th, then a part of Colonel William Tecumseh Sherman's Third Brigade, suffered heavy casualties. Their commander, Colonel James Cameron, brother of Secretary of War Simon Cameron, was killed in the fighting on Henry Hill.

After the battle, they were put to work building defensive works around Washington, digging trenches with picks and shovels. One New Yorker declared, "Spades were trumps and everyman had a full hand."

On the morning of August 14, the 79th New York rebelled, refusing to do any more work until their grievances were addressed. In addition to the back-breaking work, they were also upset that they hadn't been allowed to vote for a new colonel to lead them. Cameron's replacement, Colonel Isaac Stevens, had been appointed to lead them.

McClellan moved quickly to quash the mutiny. The 79th New York was quickly surrounded by a battalion of regular army troops with loaded firearms. The 79th gave up. Twenty-one soldiers, the ringleaders of the mutiny, were sent to prison in the Dry Tortugas.

Also on this date, in Missouri, Union General John Frémont declared martial law in St. Louis.

The 79th New York, originally organized in July 1859 as a Scottish-American fraternity in New York City, was quickly mobilized after Fort Sumter. Some recruitment brought the unit up to strength, then they marched down Broadway to Washington.

At the Battle of Bull Run, the 79th, then a part of Colonel William Tecumseh Sherman's Third Brigade, suffered heavy casualties. Their commander, Colonel James Cameron, brother of Secretary of War Simon Cameron, was killed in the fighting on Henry Hill.

After the battle, they were put to work building defensive works around Washington, digging trenches with picks and shovels. One New Yorker declared, "Spades were trumps and everyman had a full hand."

On the morning of August 14, the 79th New York rebelled, refusing to do any more work until their grievances were addressed. In addition to the back-breaking work, they were also upset that they hadn't been allowed to vote for a new colonel to lead them. Cameron's replacement, Colonel Isaac Stevens, had been appointed to lead them.

McClellan moved quickly to quash the mutiny. The 79th New York was quickly surrounded by a battalion of regular army troops with loaded firearms. The 79th gave up. Twenty-one soldiers, the ringleaders of the mutiny, were sent to prison in the Dry Tortugas.

Also on this date, in Missouri, Union General John Frémont declared martial law in St. Louis.

Friday, August 12, 2011

150 Years Ago -- Proclamations

On Monday, August 12, 1861, Confederate General Ben McCulloch issued a proclamation to the people of Missouri. McCulloch had defeated General Nathaniel Lyon's forces at the Battle of Wilson's Creek just two days before. Now he was urging Missourians to pick a side:

In Washington, President Lincoln had a proclamation of his own, declaring the last Thursday in September to be "a day of humiliation, prayer and fasting for all the people of the nation," recommending to all that they "recognize the hand of God in this terrible visitation, and in sorrowful remembrance of our own faults and crimes as a nation and as individuals, to humble ourselves before Him, and to pray for His mercy, — to pray that we may be spared further punishment, though most justly deserved; that our arms may be blessed and made effectual for the re-establishment of law, order and peace, throughout the wide extent of our country; and that the inestimable boon of civil and religious liberty, earned under His guidance and blessing, by the labors and sufferings of our fathers, may be restored in all its original excellence."

In West Texas, Mescalero Apaches raided Fort Davis, killing some cattle and scattering some horses. The Confederates now holding the fort sent Lieutenant Reuben Mays and 14 troopers in pursuit. The Apaches ambushed the cavalrymen in the Big Bend region, killing them all.

And, in Ilion, New York, Eliphalet Remington, the designer of the Remington Rifle, died of a heart attack while overseeing munitions manufacture at the E. Remington & Sons plant.

TO THE PEOPLE OF MISSOURI: Having been called by the Governor of your State to assist in driving the National forces out of the State, and restoring the people to their just rights, I have come among you simply with the view of making war upon Northern foes and to drive them back. I give the oppressed of your State an opportunity of again standing up as freemen, and uttering their true sentiments. You have been overrun and trampled upon by the mercenary hordes of the North. Your beautiful State has been nearly subjugated, but those sons of Missouri who have continued in arms, together with my forces, came back upon the enemy, and we have gained over them a great and signal victory. Their General-in-Chief is slain, and many other of their other general officers wounded; their army is in full flight, and now if the true men of Missouri will rise up and rally around their standard, the State will be redeemed.

I do not come among you to make war upon any of your people, whether of Union or otherwise. The Union people will all be protected in their rights and property. It is earnestly recommended to them to return to their homes. Prisoners of the Union party, which have been arrested by the army will be released, and allowed to return to their friends.

Missouri must be allowed to choose her own destiny. No oaths binding your consciences will be administered.

I have driven the enemy from among you. The time has now arrived for the people of the State to act. There is no time to procrastinate. She must take her position, be it North or South.

BEN MCCULLOCH, Commanding.

In Washington, President Lincoln had a proclamation of his own, declaring the last Thursday in September to be "a day of humiliation, prayer and fasting for all the people of the nation," recommending to all that they "recognize the hand of God in this terrible visitation, and in sorrowful remembrance of our own faults and crimes as a nation and as individuals, to humble ourselves before Him, and to pray for His mercy, — to pray that we may be spared further punishment, though most justly deserved; that our arms may be blessed and made effectual for the re-establishment of law, order and peace, throughout the wide extent of our country; and that the inestimable boon of civil and religious liberty, earned under His guidance and blessing, by the labors and sufferings of our fathers, may be restored in all its original excellence."

In West Texas, Mescalero Apaches raided Fort Davis, killing some cattle and scattering some horses. The Confederates now holding the fort sent Lieutenant Reuben Mays and 14 troopers in pursuit. The Apaches ambushed the cavalrymen in the Big Bend region, killing them all.

And, in Ilion, New York, Eliphalet Remington, the designer of the Remington Rifle, died of a heart attack while overseeing munitions manufacture at the E. Remington & Sons plant.

Labels:

150 Years Ago,

1861,

Abraham Lincoln,

Ben McCulloch,

Missouri

Wednesday, August 10, 2011

150 Years Ago -- The Battle of Wilson's Creek

Image via Wikipedia

Image via WikipediaOn Saturday, August 10, 1861, the Battle of Wilson's Creek was fought in southwestern Missouri.

Missouri had been a busy place during the opening months of the Civil War. Union Brigadier General Nathaniel Lyon had done much to keep Missouri in the Union, including driving secessionist-minded Governor Claiborne Jackson out of the capital and routing the state militia at the Battle of Boonville.

Now Lyon was in a precarious situation. He had pursued the militia to the southwest corner of the state, but they had been reinforced by Confederate troops -- mostly Texans and Arkansans -- under General Ben McCulloch, and now outnumbered his force 2-to-1. Lyon was now twenty miles past his advance base of Springfield and suddenly realized that he could not advance, hold his ground, or even retreat without reinforcements, but his superior, John Frémont, had very few men to send him.

The commander of the state militia, Sterling Price, saw Lyon's predicament and tried to get McCulloch to attack, but the Confederate general demurred. McCulloch had a low opinion of Price and his troops, and wasn't sure he should even be in Missouri at all. The Confederate government did not want to wage war on foreign soil, which included Missouri. McCulloch and Price argued, and Price finally told him, "You must either fight beside us or look on at a safe distance and see us fight all alone the army you dare not attack even with our aid."

Price finally won the argument and McCulloch ordered the combined Confederate/Missouri/Arkansas army to move to attack Lyon on the night of August 9. But it rained that night and McCulloch cancelled the attack.

Lyon, meanwhile, decided that the best defense is a good offense, and launched his own attack, relying on surprise to overcome his lack of numbers.

In Terrible Swift Sword, historian Bruce Catton offers a lengthy, but entertaining summary of the armies involved in the Battle of Wilson's Creek:

"It was an odd sort of army, wholly representative of its time and place. Lyon had, to begin with, a handful of regular infantry and artillery, tough and disciplined, full of contempt for volunteers, home guards, and amateur soldiers generally, whether Union or Confederate. He also had several regiments of Missouri infantry, principally German levies from St. Louis, short of equipment and training, most of them grouped in a brigade commanded by Franz Sigel. Sigel was an émigré from the German revolutionary troubles of 1848, trained as a soldier, humorless, dedicated, unhappily lacking in the capacity to lead soldiers in action; a baffling sort, devoted but incapable, who induced many Germans to enlist but who was rarely able to use them properly after they had enlisted. There were two rough-hewn regiments from Kansas and there was a ninety-day outfit from Iowa, a happy-go-lucky regiment whose time was about to expire but whose members had agreed to stick around for a few days in case the general was going to have a battle. (The Iowans did not like Lyon at all but they trusted him, considering him a tough customer and competent.) There were also stray companies and detachments from here and there whose numbers were small and whose value was entirely problematic. In miniature, this was much like the Union army that had been so spectacularly routed at Bull Run except that it was even less well equipped and disciplined.

"Yet if this army was odd the army which it was about to fight was ever so much odder -- one of the very oddest, all things considered, that ever played a part in the Civil War. Lyon's army would have struck any precisionist as something out of a military nightmare, but it was a veritable Prussian guard compared to its foes. The Southerners were armed with everything from regulation army rifles to back-country fowling pieces, a few of them wore Confederate gray but most of them wore whatever homespun garments happened to be at hand when they left home, and for at least three fourths of them there were no commissary and quartermaster arrangements whatever. The various levies were tied together by a loose gentleman's agreement rather than by any formal military organization, and many of the men were not Confederates at all, owing no allegiance to Jefferson Davis, fighting for Missouri rather than for the Confederacy. The war was still a bit puzzling, in these parts.

"The core of this army (from a professional soldier's viewpoint, at any rate) was a brigade of some 3200 Confederate troops led by Brigadier General Ben McCulloch, veteran of the Mexican War and one-time Texas Ranger, an old pal of Davy Crockett who looked the part, an officer who liked to sling a rifle over his shoulder, get on his his horse, and do his scouting personally. His men were well armed, most of them wore uniforms, and they had had about as much military training as anybody got in those days -- enough to get by on, but nothing special. There were also 2200 state troops from Arkansas, one cavalry and three infantry regiments led by Brigadier General N. B. Pearce. These men had good weapons but no uniforms and little equipment -- they carried their ammunition in their haversacks for want of better containers -- and they brought along two batteries of artillery, guns which until quite recently had been reposed in the United States arsenal at Little Rock. And, in addition, there was the Missouri State Guard under Major General Sterling Price.

"No one quite knew how many men Price had -- between 9000 and 10,000, probably, of which number only about 7000 could be used in action; the rest had no weapons at all. There were a few regimental organizations, but for the most part the formations were nothing more than bands bearing the names of the men who led them -- Wingo's infantry, Kelly's infantry, Foster's infantry, and so on. The men had no tents, no supplies, no pay, hardly any ammunition and nothing whatever in the way of uniforms; an officer could be distinguished by the fact that he would have a strip of colored flannel on his shoulders, and one of the men described General Price himself with the words: "He is a large fine looking bald fellow dressed in common citizen clothes an oald linen coat yarn pants." None of them had been given anything which West Point would have recognized as drill; one group, led by former country lawyers, was called to quarters daily by the courtroom cry of "Oyez! Oyez!" and customarily addressed its commanding officer as "Jedge." Not even in the American Revolution was there ever a more completely backwoods army; these men were not so much soldiers as rangy characters who had come down from the north fork of the creek to get into a fight. Their commissary department consisted of the nearest cornfield, and their horses got their forage on the prairie; and a veteran of the State Guard wrote after the war that any regular soldier given command of the host would have spent a solid six months drilling, equipping, organizing, and provisioning it, during which time the Yankees would have overrun every last county in Missouri once and for all. He added that although Price's men had very poor weapons -- some of them actually carried ancient flintlocks -- they knew very well how to use them, and they did not scare easily."

Sigel convinced Lyon to try a pincer movement. Lyon would split his outnumbered army, sending Sigel with 1200 men on a night march around McCulloch's army to attack his rear. Lyon, meanwhile, would march straight ahead with the remainder of the army and attack McCulloch's center and left. Everyone was in position at daybreak and the battle began.

Sigel's movement took the Confederates by surprise, driving them back, but a case of mistaken identity ruined the attack. A unit in gray uniforms approached Sigel's position. They were thought to be the 1st Iowa from Lyon's command, but turned out to be a Louisiana regiment. They closed and fired a volley that disintegrated Sigel's forces. An artillery barrage and an infantry counterattack sealed the deal. Sigel's force broke and fled.

Once Sigel's flanking move dissolved, the battle turned into a bloody, head-on attack that lasted most of the morning.

Lyon was wounded twice and had a horse shot out from under him, but he found another horse and was attempting to rally his men when he was shot through the heart. The battle gradually petered out and the Federals disengaged from the fight. They soon discovered that their highest ranking officer on the field was Major Samuel D. Sturgis of the regulars. Sturgis took command and led the army back to Springfield.

Both sides suffered about the same number of casualties -- a little over 1300 for the Federals (25% of the total present) and just over 1200 for the Confederate/Missouri/Arkansas force.

The Federals would retreat to Rolla. Price tried to get McCulloch to pursue, but he refused, concerned about his own supply line back to Arkansas. The Confederate and Arkansas troops would withdraw from the state, leaving Price to go it alone. Price would begin an invasion of northern Missouri, culminating in the Battle of Lexington on September 20.

While Price's reputation soared, Frémont's plummeted. He seemed to have lost half the state in the short time he was in command.

Related articles

- 150 Years Ago: A Meeting in St. Louis (civilwarmeanderings.blogspot.com)

- 150 Years Ago: Lyon Captures Jefferson City (civilwarmeanderings.blogspot.com)

- 150 Years Ago: Boonville and Greeneville (civilwarmeanderings.blogspot.com)

- 150 Years Ago: The Battle of Carthage (civilwarmeanderings.blogspot.com)

- 150 Years Ago -- A Lull (civilwarmeanderings.blogspot.com)

Labels:

150 Years Ago,

1861,

Ben McCulloch,

Franz Sigel,

John Fremont,

Missouri,

Nathaniel Lyon,

Sterling Price,

Wilsons Creek

Monday, August 08, 2011

150 Years Ago -- Butler Finally Gets an Answer

Image of Simon Cameron via Wikipedia

Image of Simon Cameron via WikipediaOn Thursday, August 8, 1861, Union General Benjamin Butler finally got a reply from the War Department to his July 30 inquiry. Butler had written to the War Department for instructions concerning the nine hundred fugitive slaves that had come into his lines.

Butler had argued against returning the slaves of disloyal masters, especially those that had been put to work on nearby Confederate entrenchments, claiming they were contraband of war. His wire to the War Department had focused on two important questions, "First. What shall be done with them? and, Second. What is their state and condition?"

The reply from Secretary of War Simon Cameron (in full after the jump) splits a few legal hairs, declaring, "The war now prosecuted on the part of the Federal Government is a war for the Union and for the preservation of all constitutional rights of States and the citizens of the States in the Union. Hence no question can arise as to fugitives from service within the States and Territories in which the authority of the Union is fully acknowledged. The ordinary forms of judicial proceeding which must be respected by military and civil authorities alike will suffice for the enforcement of all legal claims."

But Cameron points out that it is impossible to go through the proper legal proceedings "in States wholly or partially under insurrectionary control." Furthermore, the Confiscation Act signed into law on August 6 prohibits the return of "persons held to service" that are "employed in hostility to the United States."

Cameron orders Butler to keep and employ all fugitive slaves that come into his lines, even those from Union loyalists, and suggests that Congress will sort it all out when the war is over.

Labels:

150 Years Ago,

1861,

Benjamin Butler,

Simon Cameron,

slavery

Sunday, August 07, 2011

150 Years Ago -- The Burning of Hampton

Image of John Magruder via Wikipedia

Image of John Magruder via WikipediaOn Wednesday, August 7, 1861, a force of 500 men under Confederate General John Magruder burned the town of Hampton, Virginia.

Magruder learned from a copy of the New York Tribune, which contained a report from Union General Benjamin Butler to Secretary of War Simon Cameron, that Butler planned to use Hampton as a holding point for the thousands of runaway slaves that were coming into his lines. Butler also planned to fortify the town to protect his position at nearby Fort Monroe.

Just after midnight, Magruder's force fought off the picket force that was guarding the bridge into the town, then set about burning the town to the ground.

Magruder's force had to work quickly because they were within range of the Fort Monroe guns, but Magruder claims in his official report that "Notice was then given to the few remaining inhabitants of the place, and those who were aged or infirm were kindly cared for and taken to their friends, who occupied detached houses."

An Associated Press correspondent witnessed the episode and his account appeared in the August 31 issue of Harper's Weekly:

The greater part of the five hundred houses were built of wood, and no rain having fallen lately, the strong south wind soon produced a terrible conflagration. There were perhaps twenty white people and double that number of negroes remaining in the town from inability to move, some of whose houses were fired without waking the inmates. They gave Wilson Jones and his wife, both of them aged and infirm, but fifteen minutes to remove a few articles of furniture to the garden. Several of the whites and also of the negroes were hurried away to be pressed into the rebel service. Mr. Scofield, a merchant, took refuge in a swamp above the town. Two negroes were drowned while attempting to cross the creek. A company of rebels attempted to force the passage of the bridge, but were repulsed with a loss of three killed and six wounded.

The fire raged all night. The greater part of the rebels withdrew toward morning, and at noon to-day, when I visited the place, but seven or eight buildings were left standing.

The glare of the conflagration was so brilliant that I was enabled to write by it. A more sublime and awful spectacle has never yet been witnessed. The high south wind prevailing at the time fanned the flames into a lurid blaze, and lighted up the country for miles and miles around.

An illustration of the fire appears in the same issue.

Also on this date, the War Department entered into a contract with J. B. Eads for construction of seven ironclad river gunboats. The boats, the Cairo, Carondolet, Cincinnati, Louisville, Mound City, Pittsburg, and St. Louis, would see duty in Ulysses S. Grant's western campaigns.

Related articles

- 150 Years Ago: Alexandria and Contraband (civilwarmeanderings.blogspot.com)

- 150 Years Ago -- What Shall Be Done With Them? (civilwarmeanderings.blogspot.com)

Labels:

150 Years Ago,

1861,

Benjamin Butler,

John Magruder,

Ulysses S. Grant

Saturday, August 06, 2011

150 Years Ago -- A Lull

Events moved swiftly after the war began at Fort Sumter, but there was a lull in the aftermath of the Battle of Bull Run as both sides paused to reassess the situation. An update:

As the dog days of August 1861 began the war was starting to take shape along the border or what historian Bruce Catton called "that cross section of nineteenth-century America that ran for a thousand miles from Virginia tidewater to the plains of Kansas, reaching from the place of the nation's oldest traditions to the rude frontier where no tradition ran back farther than the day before yesterday."

In eastern Virginia, between the two capitols of Washington and Richmond, the two armies, both called the Army of the Potomac, were licking their wounds after Bull Run. The "Forward to Richmond" sentiment and the belief in a short war were over. Both commanders, George McClellan and Joe Johnston, were working hard now, organizing, drilling and equipping their men. It would be many months before they would face off again.

After resigning his commission in the U.S. Army and going south, Robert E. Lee had been put in charge of Virginia's state troops. He was briefly unemployed when those troops were put under Confederate control, but he became the top military adviser to Virginia Governor John Letcher, then to Confederate President Jefferson Davis.

Lee was sent to western Virginia to try to salvage the situation there after the Union victory at Rich Mountain. Lee arrived on August 1, charged with "combining all our forces in western Virginia on one plan of operations." Lee would soon find that it was impossible to get everyone on the same page.

The Federals had about 11,000 soldiers in the region. Brigadier General Jacob Cox commanded a force of 2700 in the Kanawha Valley. There were some small detachments in the north guarding key points along the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad, the only direct link between Washington and the West. Brigadier General William Rosecrans commanded the rest near Cheat Mountain.

Brigadier General W. W. Loring commanded the principal Confederate force, some 10,000 men, at Huntersville. Lee joined up with this contingent that was facing Rosecrans's army. Farther south, two politicians, former Virginia Governor Henry Wise and former U.S. Secretary of War John Floyd, commanded separate forces facing Cox. Wise and Floyd would spend more time competing against each other for authority than they ever would against Cox.

Farther west, the war was not being fought at all in Kentucky as both sides endeavored for a time to respect the state's proclaimed neutrality. Both sides badly needed Kentucky. Lincoln would soon remark, "I think to lose Kentucky is nearly the same as to lose the whole game." The state served as a big shield separating the two powers. A Confederate Kentucky would move the border all the way up to the Ohio River, depriving the Federals of a base from which to launch an offensive in the Mississippi Valley. If the Union took the state, Tennessee and the Mississippi River would be threatened. Neither side could afford to antagonize the state and push it to the other side, but both sides had camps either in the state or just outside its borders, rallying Kentuckians to their respective causes.

The next major conflagration of the war would take place on the far west end of the border in Missouri. Union Major General John Frémont arrived on July 25 to take command of the Department of the West.

Frémont was a career U.S. Army officer, but he had come up through the Topographical Corps, where he had become famous as "The Pathfinder," charting trails to the West. In 1856, he had become the first presidential nominee of the new Republican Party. Now he was in over his head. As Catton put it in Terrible Swift Sword, "Now he was in Missouri, a bewildering jungle where a trail could be blazed only by a man gifted with a profound understanding of the American character, the talents of a canny politician, and enormous skill as an administrator. Of these gifts General Frémont had hardly a trace."

Frémont had a big job to do, but little to do it with. He was expected to secure the state and also to organize an army and lead it down the Mississippi toward New Orleans, reopening the river to commerce and isolating the western part of the Confederacy.

He had about 23,000 troops, but about a third of those were three-month volunteers whose terms were about to expire. He was receiving new recruits, but had few arms, uniforms or other equipment, few rations and no money. Guerrilla warfare was becoming rampant in the state, and like many other commanders he was exaggerating the number of enemy troops he was facing. He thought he faced about 25,000 state militia with another 50,000 Confederate soldiers in Arkansas and Tennessee ready to invade. In actuality, he faced about half that number of both.

Nathaniel Lyon had done much to keep Missouri in the Union, but he had been blunt about it, forcing almost everyone in the state to choose sides. He had moved quickly and thwarted a plot by Governor Claiborne Jackson to capture the arsenal at St. Louis. In May, he had surrounded and captured some state militia legally encamped near St. Louis, then when he marched them through the town, it touched off a riot that left some two dozen civilians dead. One of the Missourians who had chosen a side was Sterling Price, now in charge of most of the remaining state militia. Price was fighting not so much for the Confederacy but to try to keep the war from engulfing the state.

Lyon had gone on to declare war on Price and Jackson, and had driven them away from the capital of Jefferson City. Then he had routed the militia at Boonsville and pursued them to the southwest corner of the state. His actions had allowed the Union men of the state to declare state offices vacant and to set up a new pro-Union government with Hamilton Gamble as governor. But Lyon was now in a bad predicament. He had advanced too far and was at the end of a long, precarious supply line. He wrote to Frémont, asking for reinforcements and confessing that he now could not attack, stay where he was, or even conduct an orderly retreat.

Frémont, with much to do and little to do it with, decided his best bet was to reinforce the key town of Cairo, Illinois, where the Ohio River met the Mississippi. He told Lyon to do the best he could and sent a few reinforcements, but Lyon would not see them. He would die on August 10 at the Battle of Wilson's Creek.

As the dog days of August 1861 began the war was starting to take shape along the border or what historian Bruce Catton called "that cross section of nineteenth-century America that ran for a thousand miles from Virginia tidewater to the plains of Kansas, reaching from the place of the nation's oldest traditions to the rude frontier where no tradition ran back farther than the day before yesterday."

In eastern Virginia, between the two capitols of Washington and Richmond, the two armies, both called the Army of the Potomac, were licking their wounds after Bull Run. The "Forward to Richmond" sentiment and the belief in a short war were over. Both commanders, George McClellan and Joe Johnston, were working hard now, organizing, drilling and equipping their men. It would be many months before they would face off again.

After resigning his commission in the U.S. Army and going south, Robert E. Lee had been put in charge of Virginia's state troops. He was briefly unemployed when those troops were put under Confederate control, but he became the top military adviser to Virginia Governor John Letcher, then to Confederate President Jefferson Davis.

Lee was sent to western Virginia to try to salvage the situation there after the Union victory at Rich Mountain. Lee arrived on August 1, charged with "combining all our forces in western Virginia on one plan of operations." Lee would soon find that it was impossible to get everyone on the same page.

The Federals had about 11,000 soldiers in the region. Brigadier General Jacob Cox commanded a force of 2700 in the Kanawha Valley. There were some small detachments in the north guarding key points along the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad, the only direct link between Washington and the West. Brigadier General William Rosecrans commanded the rest near Cheat Mountain.

Brigadier General W. W. Loring commanded the principal Confederate force, some 10,000 men, at Huntersville. Lee joined up with this contingent that was facing Rosecrans's army. Farther south, two politicians, former Virginia Governor Henry Wise and former U.S. Secretary of War John Floyd, commanded separate forces facing Cox. Wise and Floyd would spend more time competing against each other for authority than they ever would against Cox.

Farther west, the war was not being fought at all in Kentucky as both sides endeavored for a time to respect the state's proclaimed neutrality. Both sides badly needed Kentucky. Lincoln would soon remark, "I think to lose Kentucky is nearly the same as to lose the whole game." The state served as a big shield separating the two powers. A Confederate Kentucky would move the border all the way up to the Ohio River, depriving the Federals of a base from which to launch an offensive in the Mississippi Valley. If the Union took the state, Tennessee and the Mississippi River would be threatened. Neither side could afford to antagonize the state and push it to the other side, but both sides had camps either in the state or just outside its borders, rallying Kentuckians to their respective causes.

The next major conflagration of the war would take place on the far west end of the border in Missouri. Union Major General John Frémont arrived on July 25 to take command of the Department of the West.

Frémont was a career U.S. Army officer, but he had come up through the Topographical Corps, where he had become famous as "The Pathfinder," charting trails to the West. In 1856, he had become the first presidential nominee of the new Republican Party. Now he was in over his head. As Catton put it in Terrible Swift Sword, "Now he was in Missouri, a bewildering jungle where a trail could be blazed only by a man gifted with a profound understanding of the American character, the talents of a canny politician, and enormous skill as an administrator. Of these gifts General Frémont had hardly a trace."

Frémont had a big job to do, but little to do it with. He was expected to secure the state and also to organize an army and lead it down the Mississippi toward New Orleans, reopening the river to commerce and isolating the western part of the Confederacy.

He had about 23,000 troops, but about a third of those were three-month volunteers whose terms were about to expire. He was receiving new recruits, but had few arms, uniforms or other equipment, few rations and no money. Guerrilla warfare was becoming rampant in the state, and like many other commanders he was exaggerating the number of enemy troops he was facing. He thought he faced about 25,000 state militia with another 50,000 Confederate soldiers in Arkansas and Tennessee ready to invade. In actuality, he faced about half that number of both.

Nathaniel Lyon had done much to keep Missouri in the Union, but he had been blunt about it, forcing almost everyone in the state to choose sides. He had moved quickly and thwarted a plot by Governor Claiborne Jackson to capture the arsenal at St. Louis. In May, he had surrounded and captured some state militia legally encamped near St. Louis, then when he marched them through the town, it touched off a riot that left some two dozen civilians dead. One of the Missourians who had chosen a side was Sterling Price, now in charge of most of the remaining state militia. Price was fighting not so much for the Confederacy but to try to keep the war from engulfing the state.

Lyon had gone on to declare war on Price and Jackson, and had driven them away from the capital of Jefferson City. Then he had routed the militia at Boonsville and pursued them to the southwest corner of the state. His actions had allowed the Union men of the state to declare state offices vacant and to set up a new pro-Union government with Hamilton Gamble as governor. But Lyon was now in a bad predicament. He had advanced too far and was at the end of a long, precarious supply line. He wrote to Frémont, asking for reinforcements and confessing that he now could not attack, stay where he was, or even conduct an orderly retreat.

Frémont, with much to do and little to do it with, decided his best bet was to reinforce the key town of Cairo, Illinois, where the Ohio River met the Mississippi. He told Lyon to do the best he could and sent a few reinforcements, but Lyon would not see them. He would die on August 10 at the Battle of Wilson's Creek.

Labels:

150 Years Ago,

1861,

Eastern Theater,

George McClellan,

Jacob Cox,

John Fremont,

Joseph E. Johnston,

Kentucky,

Missouri,

Nathaniel Lyon,

Robert E. Lee,

western Virginia,

William Rosecrans

Wednesday, August 03, 2011

150 Years Ago -- The First Aircraft Carrier

Image of John LaMountain via Wikipedia

Image of John LaMountain via WikipediaOn Saturday, August 3, 1861, the concept of the aircraft carrier was born as balloonist John LaMountain began making tethered ascents from the deck of the Union tug Fanny, anchored in Hampton Roads near Fort Monroe, Virginia.

LaMountain would also make the first night ascension on August 10. He counted the campfires and tent lights he saw in an effort to determine the enemy's strength.

LaMountain competed with Thaddeus S. C. Lowe to become Chief Aeronaut of the Union Army Balloon Corps. Lowe would win the competition, but an agreement was worked out wherein LaMountain would continue his work independent of Lowe, but would cooperate with him if necessary.

Labels:

150 Years Ago,

1861,

John LaMountain,

Thaddeus Lowe

Tuesday, August 02, 2011

150 Years Ago -- Dug Springs

On Friday, August 2, 1861, the Battle of Dug Springs took place in Missouri. Events were rapidly coming to a head in the state.

Union General Nathaniel Lyon had declared war on Governor Claiborne Jackson and Sterling Price, the commander of the state militia. He drove them away from Jefferson City, the state capital, routed the militia at Boonville, and pursued them to the southwest corner of the state.

Now Lyon was in a precarious situation. He was in Springfield, far from his home base of St. Louis, and outnumbered. Price's militia had joined with Confederate troops from Arkansas under General Ben McCulloch, giving them about a 2-to-1 advantage over Lyon. Also, many of Lyon's men were leaving or preparing to leave as their 90-day enlistments ran out.

On August 1, Lyon got the news that the large Southern force was advancing on his position. There were said to be three columns of troops with the main column advancing up the Wire road (named for the telegraph wires that lined it).

Lyon would have been wise to retreat, but did not want to do so without a fight. He put his forces on the road to meet this threat. They camped 12 miles south of Springfield that night, and continued the march the next morning. Lyon planned to attack the main column, and if all went well, take on the other columns in turn.

Advance units from the opposing forces ran into each other at 9 a.m. on August 2 on the Wire road. The Battle of Dug Springs lasted for about five hours, ebbing back and forth as both sides cautiously launched probing attacks to determine the size of the force they faced. Although he was outnumbered by the combined Southern forces, Lyon had the advantage with the troops that were present for this fight. His vanguard, composed of U.S. Army regulars, faced six companies of Missouri State Guard troops under General James Rains.

Eventually, a charge by troops from the 2nd U.S. Infantry scattered Rains's men, and they retreated back down the Wire road. The Southerners would call the battle "Rains' Scare," and it would reinforce McCulloch's low opinion of the fighting abilities of the Missouri troops, but they would regroup and continue the advance. Lyon would plan one more attack. The armies would meet on August 10 at Wilson's Creek.

Also on this date, Colonel William Tecumseh Sherman was promoted to brigadier general, dated from May 17. He was transferred to Kentucky where he was second in command under General Robert Anderson, the hero of Fort Sumter.

And, the U.S. Congress voted to impose the first national income tax. In addition to new tariffs, the bill called for a flat tax of 3% on income over $800 to help finance the war. President Lincoln would sign the bill into law on August 5. The Revenue Act of 1861 would be repealed by the Revenue Act of 1862, which replaced the flat rate with a progressive scale -- 3% on income over $600 and 5% on income over $10,000.

Union General Nathaniel Lyon had declared war on Governor Claiborne Jackson and Sterling Price, the commander of the state militia. He drove them away from Jefferson City, the state capital, routed the militia at Boonville, and pursued them to the southwest corner of the state.

Now Lyon was in a precarious situation. He was in Springfield, far from his home base of St. Louis, and outnumbered. Price's militia had joined with Confederate troops from Arkansas under General Ben McCulloch, giving them about a 2-to-1 advantage over Lyon. Also, many of Lyon's men were leaving or preparing to leave as their 90-day enlistments ran out.

On August 1, Lyon got the news that the large Southern force was advancing on his position. There were said to be three columns of troops with the main column advancing up the Wire road (named for the telegraph wires that lined it).

Lyon would have been wise to retreat, but did not want to do so without a fight. He put his forces on the road to meet this threat. They camped 12 miles south of Springfield that night, and continued the march the next morning. Lyon planned to attack the main column, and if all went well, take on the other columns in turn.

Advance units from the opposing forces ran into each other at 9 a.m. on August 2 on the Wire road. The Battle of Dug Springs lasted for about five hours, ebbing back and forth as both sides cautiously launched probing attacks to determine the size of the force they faced. Although he was outnumbered by the combined Southern forces, Lyon had the advantage with the troops that were present for this fight. His vanguard, composed of U.S. Army regulars, faced six companies of Missouri State Guard troops under General James Rains.

Eventually, a charge by troops from the 2nd U.S. Infantry scattered Rains's men, and they retreated back down the Wire road. The Southerners would call the battle "Rains' Scare," and it would reinforce McCulloch's low opinion of the fighting abilities of the Missouri troops, but they would regroup and continue the advance. Lyon would plan one more attack. The armies would meet on August 10 at Wilson's Creek.

Also on this date, Colonel William Tecumseh Sherman was promoted to brigadier general, dated from May 17. He was transferred to Kentucky where he was second in command under General Robert Anderson, the hero of Fort Sumter.

And, the U.S. Congress voted to impose the first national income tax. In addition to new tariffs, the bill called for a flat tax of 3% on income over $800 to help finance the war. President Lincoln would sign the bill into law on August 5. The Revenue Act of 1861 would be repealed by the Revenue Act of 1862, which replaced the flat rate with a progressive scale -- 3% on income over $600 and 5% on income over $10,000.

Monday, August 01, 2011

150 Years Ago -- Robert E. Lee and John Baylor

On Thursday, August 1, 1861, Robert E. Lee arrived in western Virginia. After the recent defeats in the area, Lee had been sent by Confederate President Jefferson Davis to inspect the Confederate forces and to coordinate a counteroffensive. Lee would soon take command of the troops, supplanting General W. W. Loring.

Out west, John Baylor claimed the New Mexico Territory below the 34th parallel (the southern half of present-day New Mexico and Arizona) for the Confederacy. Baylor proclaimed himself the military governor of the new Confederate Arizona Territory and issued a proclamation:

Out west, John Baylor claimed the New Mexico Territory below the 34th parallel (the southern half of present-day New Mexico and Arizona) for the Confederacy. Baylor proclaimed himself the military governor of the new Confederate Arizona Territory and issued a proclamation:

"Proclamation to the People of the Territory of Arizona: The social and political condition of Arizona being little short of general anarchy, and the people being literally destitute of law, order, and protection, the said Territory, from the date hereof, is hereby declared temporarily organized as a military government until such time as Congress may otherwise provide.

I, John R. Baylor, lieutenant-colonel, commanding the Confederate Army in the Territory of Arizona, hereby take possession of said Territory in the name and behalf of the Confederate States of America. For all purposes herein specified, and until otherwise decreed or provided, the Territory of Arizona shall comprise all that portion of New Mexico lying south of the thirty-fourth parallel of north latitude."

Labels:

150 Years Ago,

1861,

Arizona,

John Baylor,

Robert E. Lee,

western Virginia

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)