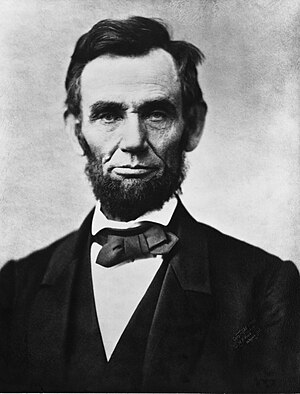

Image via Wikipedia

Image via WikipediaOn Thursday, July 4, 1861, in the midst of the patriotic celebrations that were going on in the North and the South, the 37th Congress of the United States met in special session. Abraham Lincoln wrote an address which was read to a joint session to give an accounting of the war measures he had taken, to outline the causes and purpose of the conflict, and to ask Congress to appropriate the men and money necessary to continue the war.

On April 15, when Lincoln declared war against the South and called out the militia, he also called for a special session of Congress. It had been a "called in haste to convene at leisure" call though; Lincoln had given them 80 days to convene. Until they did, the response of the Federal government's was solely up to Lincoln.

Lincoln had proclaimed war, called out the militia, suspended habeas corpus, blockaded the Southern coast, called for 42,000 three-year volunteers, greatly increased the regular army and navy; all of this committing the government to spend vast sums of money. Now, the 80 days was up and Lincoln was justifying what he had done and asking Congress to give its authorization after the fact.

He was not too worried about the outcome. His own Republican Party controlled both houses of Congress -- with 32 of the 48 senators and 106 of the 176 congressmen. Also, it would be hard for Congress to vote against any wartime measures in the midst of all the preparations for war that were then going on.

Lincoln began with a recap of everything that had happened so far: the suspension of federal functions within the seceded states, the seizure of federal property, the "firing on bread" at Fort Sumter. He declared that the South had "forced upon the country the distinct issue, 'Immediate dissolution or blood.'"

And this issue embraces more than the fate of these United States. It presents to the whole family of man the question whether a constitutional republic, or democracy—a government of the people by the same people—can or can not maintain its territorial integrity against its own domestic foes. It presents the question whether discontented individuals, too few in numbers to control administration according to organic law in any case, can always, upon the pretenses made in this case, or on any other pretenses, or arbitrarily without any pretense, break up their government, and thus practically put an end to free government upon the earth. It forces us to ask, Is there in all republics this inherent and fatal weakness? Must a government of necessity be too strong for the liberties of its own people, or too weak to maintain its own existence?

So viewing the issue, no choice was left but to call out the war power of the Government and so to resist force employed for its destruction by force for its preservation...

Other calls were made for volunteers to serve three years unless sooner discharged, and also for large additions to the Regular Army and Navy. These measures, whether strictly legal or not, were ventured upon under what appeared to be a popular demand and a public necessity, trusting then, as now, that Congress would readily ratify them. It is believed that nothing has been done beyond the constitutional competency of Congress.

As for suspending the writ of habeas corpus...

This authority has purposely been exercised but very sparingly. Nevertheless, the legality and propriety of what has been done under it are questioned, and the attention of the country has been called to the proposition that one who is sworn to "take care that the laws be faithfully executed" should not himself violate them. Of course some consideration was given to the questions of power and propriety before this matter was acted upon. The whole of the laws which were required to be faithfully executed were being resisted and failing of execution in nearly one-third of the States. Must they be allowed to finally fail of execution, even had it been perfectly clear that by the use of the means necessary to their execution some single law, made in such extreme tenderness of the citizen's liberty that practically it relieves more of the guilty than of the innocent, should to a very limited extent be violated? To state the question more directly, Are all the laws but one to go unexecuted, and the Government itself go to pieces lest that one be violated? Even in such a case, would not the official oath be broken if the Government should be overthrown when it was believed that disregarding the single law would tend to preserve it? But it was not believed that this question was presented. It was not believed that any law was violated. The provision of the Constitution that "the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus shall not be suspended unless when, in cases of rebellion or invasion, the public safety may require it" is equivalent to a provision—is a provision—that such privilege may be suspended when, in cases of rebellion or invasion, the public safety does require it. It was decided that we have a case of rebellion and that the public safety does require the qualified suspension of the privilege of the writ which was authorized to be made. Now it is insisted that Congress, and not the Executive, is vested with this power; but the Constitution itself is silent as to which or who is to exercise the power; and as the provision was plainly made for a dangerous emergency, it can not be believed the framers of the instrument intended that in every case the danger should run its course until Congress could be called together, the very assembling of which might be prevented, as was intended in this case, by the rebellion.

Lincoln went on to ask Congress for "the legal means for making this contest a short and a decisive one," for 400,000 men and $400 million. The contest was now more than a local disturbance of "combinations to powerful to resist" that some 90-day militia could handle.

A right result at this time will be worth more to the world than ten times the men and ten times the money. The evidence reaching us from the country leaves no doubt that the material for the work is abundant, and that it needs only the hand of legislation to give it legal sanction and the hand of the Executive to give it practical shape and efficiency. One of the greatest perplexities of the Government is to avoid receiving troops faster than it can provide for them. In a word, the people will save their Government if the Government itself will do its part only indifferently well.

After expounding on some of same themes he had explored in his First Inaugural Address of the myth of state sovereignty and states rights and the illegality of secession, Lincoln got to the purpose of the war, declaring...

This is essentially a people's contest. On the side of the Union it is a struggle for maintaining in the world that form and substance of government whose leading object is to elevate the condition of men; to lift artificial weights from all shoulders; to clear the paths of laudable pursuit for all; to afford all an unfettered start and a fair chance in the race of life. Yielding to partial and temporary departures, from necessity, this is the leading object of the Government for whose existence we contend...

Our popular Government has often been called an experiment. Two points in it our people have already settled—the successful establishing and the successful administering of it. One still remains—its successful maintenance against a formidable internal attempt to overthrow it. It is now for them to demonstrate to the world that those who can fairly carry an election can also suppress a rebellion; that ballots are the rightful and peaceful successors of bullets, and that when ballots have fairly and constitutionally decided there can be no successful appeal back to bullets; that there can be no successful appeal except to ballots themselves at succeeding elections. Such will be a great lesson of peace, teaching men that what they can not take by an election neither can they take it by a war; teaching all the folly of being the beginners of a war.

Lincoln started using the third person to describe himself, "the Executive," and concluded by saying...

It was with the deepest regret that the Executive found the duty of employing the war power in defense of the Government forced upon him. He could but perform this duty or surrender the existence of the Government...

As a private citizen the Executive could not have consented that these institutions shall perish; much less could he in betrayal of so vast and so sacred a trust as these free people had confided to him. He felt that he had no moral right to shrink, nor even to count the chances of his own life in what might follow. In full view of his great responsibility he has so far done what he has deemed his duty. You will now, according to your own judgment, perform yours. He sincerely hopes that your views and your action may so accord with his as to assure all faithful citizens who have been disturbed in their rights of a certain and speedy restoration to them under the Constitution and the laws.

Congress would end up giving Lincoln 25% more than he asked for, 500,000 men and $500,000,000

No comments:

Post a Comment